Egyptian cobra

Naja haje (Linnaeus, 1758)

By Raúl León Vigara

Updated: 9/05/2013

Taxonomy: Serpentes | Elapidae | Naja | Naja haje

Naja haje

Naja haje

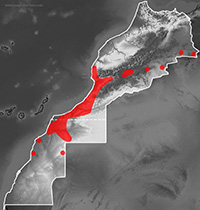

Distribution map of

Naja haje

in Morocco.

Gallery: 5 photos. [ENTER]

Phylogenetic frame

It is the only species of Ophidians classified in the Elapidae order living in the research area.

In 1989, Jose Antonio Valverde described the subspecies “legionis” for those specimens of Naja haje found in Morocco, based on three characteristics: color, pholidosis and genetic isolation. However, subsequent genetic and morphological researches do not consider Naja haje legionis as an acceptable subspecies, due to the slight variation shown by the specimens of this research area in comparison with the nominate former species. (Broadley y Wüster, 2004; J.F. Trapé et al., 2009). Therefore, the cobras found in the research area are classified as Naja haje haje, considering the “legionis” as an indicative of “form” or “morph” related to color.

Description

Undoubtedly, watching the Egyptian cobra in its habitat is one of the most astonishing and impressive shows in the Maghreb. This impressive ophidian does not normally exceed the 160 cm long in this North African area (Bons and Geniez, 1996), even though specimens of 181 cm have been recorded. (Valverde, 1989).

The shape of its body is cylindrical, long and proportioned.

There are notable differences in color and pattern between juvenile and adult specimens.

At the first stage of their lives, right after they are given birth, small cobras are of a pale yellow color with a brownish spotty pattern all over their bodies and, their heads, necks and front of the body are of a bright black color. When it expands its hood, it can be observed how in the ventral area of its neck there are big yellow spots within the black pigmentation.

Juvenile specimens are commonly yellow, copper-yellow, orange-yellow, reddish, covered by black and/or brown spots. The black color is found on the head, neck and the third of its body front, including the ventral area. The ventral area in the rest of the body has the same base color of the dorsal area.

As the Egyptian cobra grows up, its black color spreads on its entire body, restricting the yellow color to the dorsal scales lines nearest to the ventral scales. At its adult stage they are black in both dorsal and ventral areas. However, adult specimens can also be dark brown mixed with black, grayish-black, etc.

Izquierda: Juvenil. Guelmim. Foto: © Raúl León.

Right: Adult. Guelmim. Photo: © Javier Gállego.

The head is not differentiated from its neck and it has a rounded snout. The eyes are of a dark color and its pupils are hardly distinguished.

Males are longer than females (Schleich, 1996).

It lays between 8 to 20 eggs in a place where adequate conditions are found as for example: under great blocks of stone, carved trunks, holes, etc. (Gruber, 1993).

In the research area there are some ophidians that can be confused with cobra by visitors and inhabitants. Let us try to clarify these confusions:

Regarding color, juvenile Egyptian cobra can be confused with North African Catsnake (Telescopus tripolitanus), as this snake has black head and neck and a dark colored body (brown, orange or red, normally). To differentiate this snake from a juvenile cobra we must know that the North African Catsnake has the black pigments just on the head and neck areas not expanding over the bodyfront as in the juvenile cobras. The eyes are big and noticeable, round shaped and standing out the ophidian head; also, its pupils are elliptical or vertical, whereas cobras have round shaped pupils. The Old World catsnake has its head well differentiated from its neck as it does not happen with the Egyptian cobra. Catsnakes have bright, beige or dark-white ventral scales, which means a different pattern from its dorsal scales, as the Egyptian cobra has the same color in the ventral scales and dorsal scales.

Comparison between Egyptian cobra (Naja haje) and North African Catsnake (Telescopus tripolitanus), to help avoid confusion.

Top left: Naja haje, juvenile. Guelmim. Photo: © Raúl León.

Top right: Telescopus tripolitanus. Assa. Photo: © Gabri Mtnez.

Bottom left: Naja haje, juvenile. Guelmim. Photo: © Raúl León.

Bottom right: Telescopus tripolitanus detail. Assa. Photo: © Raúl León.

Adult specimens of Egyptian cobra and African House Snake (Boaedon fuliginosus) can also be confused as both species have a dark and smooth color. African House Snake have smaller body scales and less noticeable than in the Egyptian cobra, which are bigger and marked, with a brighter aspect; African House Snake are not as dark as adult cobras, they are usually brown or dark brown, its ventral scales are pearly white and its labial scales of a bright color, something not happening in an Egyptian cobra. African House Snake reflect light and so they have a brighter aspect than the Egyptian cobra and they show iridiscence. Eyes can be differentiated as African House Snake have bigger eyes with vertical pupils and cobras do not.

Comparison between Egyptian cobra (Naja haje) and African House Snake (Boaedon fuliginosus), to help avoid confusion.

Top left: Naja haje. Guelmim. Photo: © J. Gállego.

Top right: African House Snake (Boaedon fuligonosus). Tan-Tan. Photo: © J. Gállego.

Bottom left: Naja haje, juvenile. Guelmim. Photo: © Raúl León.

Bottom right: Boaedon fuligonosus, detail. Tan-Tan. Photo: © J. Gállego.

There exists a colubrid inhabiting the research area showing a quite intimidating attitude, similar to that of the Egyptian cobra. It is the so called Moila Snake (Rhageris moilensis) which when it feels in danger it flattens its neck -as a cobra does- though it rarely lifts its first third of the body as cobra does. At first sight, the color of the body could seem similar to that of juvenile Egyptian cobra specimens, though Moila Snake is not black on the head and on the first third of the body. Hence, it is easy to differentiate it from the cobra.

Left: The Moila snake ( Rhagerhis moilensis) shows a body coloration similar to Egyptian cobra juveniles, but does not show the head, neck and body first third of tplain black, be so easy to differentiate juveniles. Guelmim. Photo: © Raúl León. Right: The Moila snake shows a very similar intimidating strategy, flattened dorso-ventrally neck cap-shaped, hence its common name: False cobra. Guelmim. Photo: © Raúl León.

The Elapidae family -in which cobra is- includes those snakes with proteroglyphous fangs (fixed in the upper jaws, enabling the snake to release the venom). Egyptian Cobra releases neurotoxic venom.

Ecology and habits

It is a mainly nocturnal species though has been found active during day time (Schleich, 1996).

Adults establish their territory where they normally live for many years, adopting different shelters nearby as creeks, abandoned mammals´ burrows, etc., where they do their thermoregulation (Schleich, 1996). It is a fast species. It has been found climbing up trees. (Schleich, 1996). It is actively looking for its prey. Its food range is ample and varied: toads, frogs, saurian, ophidians, birds, eggs and small mammals. (Schleich, 1996).

If Egyptian Cobra feels menaced it tries to run away or go unnoticed, if the menace continues, this species can use different ways of defense. The most notorious and intimidating strategy is the vertical lifting and the flattening of the dorsal and ventral areas in the front of the body, expanding its hood by widening the ribs located in this area of the body. This is an alert and defense attitude projected by the snake as well as an illusion of being bigger.

If menace still continues, the Egyptian cobra opens the mouth showing its bluish white color in the inside preventing its predator from keeping away if it does not want to be bitten.

As a last resource before a dangerous situation, cobra may take the option to bite, inoculating its venom or just by a “dry bite” (when no venom is inoculated).

Left: Naja haje adult expanding the cap on intimidating attitude. Guelmim. Photo: © J. Gállego.

Right: North African Cobra juvenile in intimidatory attitude: the first third of the body upright, expanding the cap and opening the mouth. Guelmim. Photo: © Raúl León.

Egyptian cobra releases neurotoxic venom which is considered highly dangerous for humans and even mortal. Therefore it is important not to bother or manipulate them in order to avoid an occasional bite.

Distribution, habitat and abundance

Mainly found in Agadir, Ouarzazate and El-Aaiún, going through the Anti-Atlas to Figuig (Bons and Geniez, 1996). The Naja haje specimens found in the research area may come from Egypt. (Valverde, 1989). Genetic analyses group them quite near to Egyptian and western African cobras. (Trapé et al., 2009).

They live in dry areas with warm winters. (Bons and Geniez, 1996). It develops its activity in different types of habitats, from flat areas with scarce vegetation to more accidental and rocky formations, as vegetation-covered river oueds, rocky arid areas with vegetation or not, argane woodlands (Argania spinosa), etc. (Valverde, 1989; Bons and Geniez, 1996).

Egyptian cobra is considered as one of the most endangered species in the area. This sad reality makes at the same time to be highly appreciated and exciting when it is found in its natural habitat.

It is the most intensively researched snake by the Aïssaouas “snake hunters” who capture them and after that they use them for the shows or sell them to local “snake charmers” who exhibit the snakes at the squares of the different Moroccan cities, mainly in Marrakech. The result is that some 500 cobras per year are captured and removed from their habitats. (Feriche, unpublished). Nowadays, the number could be higher, as the increase in tourism means an increase in exhibitions and therefore an increase in captures. (Feriche, unpublished). People who carry out this activity make their livings out of it, which for the preservation of the Egyptian cobra is quite a serious task, as it means a direct conflict with the interests of a highly economically-depressed local population. The snake hunters say that the year that there is a plague of migratory locust and fields are sprayed, they find very few cobra specimens. (Feriche, unpublished). This information can give us an idea on how these toxic products could be seriously affecting directly on the whole fauna or through the food chain. Consequently we could say that Egyptian cobras are highly menaced by human activities. As an addition to this there are many specimens killed by local people -scared by the danger this snake represents-; less frequently found killed on the road or those that die from starvation after falling into pits, water reservoirs, etc.

In other parts of the world and before a situation of conflict like this one, they have chosen alternatives that benefit both: local population and snakes. Therefore it would be interesting an increase of alternatives which would probably succeed, -based on those experiences- by offering a different way of managing this task as a feasible and real alternative much better and wiser than exterminating the ancient practice of exhibiting ophidians in this area.

Translated by Carlos Perez Fontán-Membrives.

References

- Bons, J. y Geniez, P. 1996. Anfibios y Reptiles de Marruecos (incluyendo Sáhara Occidental). Atlas Biogeográfico. Asociación Herpetológica Española. Barcelona. 319 pp

- Feriche, M. inédito. Aissouas, los encantadores de serpientes.

- Gruber, U. 1993. Guía de las serpientes de Europa, Norte de África y Próximo Oriente. Omega. Barcelona. 247 pp.

- Valverde, J.A., 1989. Notas sobre vertebrados. V11, Una nueva cobra del NW de África, Naja haje legionis, ssp nov. (Elapidae, Serpentes). Actas de las IX Jornadas. Estación Biológica de Doñana. 214-230

- Schleich, H. H., Kästle, W., Kabisch, K. 1996. Amphibians and Reptiles of North Africa. Koeltz Sci. Books, Koenigstein.

- Trape, J.-F., Chirio, L., G. Broadley, D. G. y Wüster, W., 2009. Phylogeography and systematic revision of the Egyptian cobra (Serpentes: Elapidae: Naja haje) species complex, with the description of a new species from West Africa. Zootaxa 2236: 1–25

- Trape, J.-F. y Mané, Y. 2006. Guide des serpents d’Afrique occidentale. Savane et désert. IRD Editions, Paris, 226 pp.

To cite this page:

Raúl León Vigara (2013): Naja haje (Linnaeus, 1758). In: Martínez, G., León, R., Jiménez-Robles, O., González De la Vega, J. P., Gabari, V., Rebollo, B., Sánchez-Tójar, A., Fernández-Cardenete, J. R., Gállego, J. (Eds.). Moroccoherps. Amphibians and Reptiles of Morocco and Western Sahara. Available from www.moroccoherps.com/en/ficha/Naja_haje/. Version 9/05/2013.

To cite www.morocoherps.com en as a whole:

Martínez, G., León, R., Jiménez-Robles, O., González De la Vega, J.P., Gabari, V., Rebollo, B., Sánchez-Tójar, A., Fernández-Cardenete, J.R., Gállego, J. (Eds.). Moroccoherps. Amphibians and Reptiles of Morocco and Western Sahara. Available from www.moroccoherps.com.