Common Chameleon

Chamaeleo chamaeleon (Linnaeus, 1758)

By Juan Pablo González de la Vega

Updated: 23/09/2012

Taxonomy: Sauria | Chamaeleonidae | Chamaeleo | Chamaeleo chamaeleon

Chamaeleo chamaeleon

Chamaeleo chamaeleon

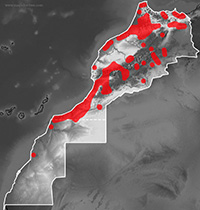

Distribution map of

Chamaeleo chamaeleon

in Morocco.

Gallery: 16 photos, 1 video file. [ENTER]

Description

This reptile’s body is arched and very compressed laterally; the limbs are long and slender and it has prehensile tail generally of length equal to or shorter than the rest of the body, with an unusually variable background color (which it has the power to change). All these traits make the species, and particularly the common chameleon, distinctive and well known to all.

The head is distinct from the body; it is pointed and has two small occipital lobes on each side of a prominent crest. The eyes are very prominent, with circular eyelids, and are located on either side of the head. The eye movements are independent of each other, and they are able to look at different places at once (stereoscopic vision). The tongue is retracted into a bag like cavity in the bottom of the mouth and can be projected with great precision and breathtaking speed for a distance as long as the total length of the individual. The chameleon catches her prey (insects and small vertebrates), with her club-shaped and sticky tongue. There is no external ear and nostrils are small. The juveniles are similar in appearance and coloration to adults, but unlike adults, their heads are rounded and have a black palate, especially newborns.

Details of the species as found in the province of Huelva, Andalucia (Spain).

From left to right and top to bottom:

Adult, ventral view. El Portil (Huelva). Photo: © V. Gabari.

Specimen found basking in December. Nuevo Portil (Huelva). Photo: © J. P. González de la Vega.

Adult Female detail . Palos de la Frontera (Huelva). Photo: © J. P. González de la Vega.

Adult. El Rompido (Huelva). Photo: © B. Rebollo Fernández.

Cráneo de adulto, detalles. El Portil (Huelva). Photo: © J. P. González de la Vega.

Adult found sleeping. El Portil (Huelva). Photo: © J. P. González de la Vega.

Adult male in aggressive-defensive position. Punta Umbría (Huelva). Photo: © J. P. González de la Vega.

Adult female in aggressive-defensive position. Palos de la Frontera (Huelva). Photo: © J. P. González de la Vega.

The background color varies due to their being able to change it according to circumstances, so that any given individual can be green, yellow, brown and even black or extremely blue (during the early hours of the coldest months) before or after hibernation. Along with the prevailing color, there are always two dashed yellow or brown stripes, and a series of ocelli or macules, some whitish and others in dark colors. Color variations are a true testament to the mood of the specimen, environmental factors, reproductive state, and even the social position occupied by each individual with respect to their peers; these changes are made by special cells in the skin called chromatophores.

Left : Adult male. Right: detail. Noftia. Photos: © Gabri Mtnez.

Generally dominant males have a bright green, while muted tones prevail in less dominant males. The fertilized females take on a dark blue color stained yellow. At night while they sleep they are typically neutral tones. In the presence of large specimens juveniles turn black. The belly is always bisected with white or cream stripe, starting from the nose and reaching to the end of the tail. Chameleons are not like other lizards, and if the tail is amputated it will not regrow. The tail is used like a fifth limb to hold the chameleon in the bushes to help access food or to assist with moving through the branches. When at rest or sleep during the night, it is often held coiled in a spiral.

The limbs are long, slender, ending in powerful claws used like tweezers to grasp branches and climb. The fingers are opposed three to two according to the direction of travel, ie the forelegs have three fingers inside, while the rear have only two. Although normally between 190 and 250 mm long, it is not rare to find specimens reaching 300 mm in total length.

Adult Male. Mohamed V Reservoir. Photos: © J. P. González de la Vega.

Ecology and habits

It is predominantly a diurnal reptile with arboreal habits, its movements slow and rhythmic; it is solitary and very territorial, especially the male in the mating season. In the presence of another male, the male chameleon flattens his body to appear larger, at the same time opening his mouth, the throat swells and he moves the body rhythmically, emitting a characteristic sound. If the opponent does not choose to leave the territory, the dominant male expels it by inflicting strong bites.

Feeling exposed, it will completely flatten its body and hide behind branches. If we try to capture it, it takes flight and if necessary releases the branch dropping into the foliage or directly to the ground. After being caught, it opens it mouth widely and attempts to give a strong bite, but it soon gets used to our presence and stops.

Chameleons usually live near any growing tree, shrub or vegetation. In areas where the vegetation is sparse or nonexistent, they can be found by lifting small piles of stones under which they find shelter, but always near an area of water even if the presence of water is temporary.

The strategy of the chameleon’s approach with enemies may be summarized as “the art of seeing without being seen and eating without being eaten.” Its main weapon is to remain absolutely still and to blend perfectly with the environment to go completely unnoticed.

When moving along the ground, eg when moving from one tree or bush to another, and much more frequently during the breeding season, it does so slowly, with the tail raised and with very slow movements and a characteristic rhythmic motion leaving only footprints. If it has to move at speed you will also see the track of the tail.

Its food is mainly insectivorous, capturing all kinds of insects as long as they fit into the mouth. It can also prey on small lizards, caught with his long tongue.

Sex differences in males include greater prominence and height of the helmet or back of the head and the tail length is greater than in females. Females generally reach larger and size and are more robust.

The breeding season extends from July through October, during this time the males become more aggressive with their peers, especially when courting females. For mating, the female is held with a bloodless bite on the back or stomach, or (if the female is receptive) just held with their limbs, remaining in this position for the few minutes it takes to complete intercourse. If a female becomes pregnant they present a typical coloration of dark blue simply sprinkled with yellow spots, which indicates their status to their peers. If a male tries to approach a female once fertilized, he will be ruthlessly expelled from the vicinity of its territory with the signature back and forth movements, snorting and strong bites.

Genetic studies (Paulo et al., 2002), reveal that the southern populations of the Iberian Peninsula are genetically indistinguishable from those of Morocco, coming from recent anthropogenic introductions, so this entry includes photographs and details of these Iberian populations.

Reproductive features of the common chameleon in the province of Huelva, Andalucía (Spain).

From left to right and from top to bottom:

Pregnant female. Mazagón (Huelva).

Pregnant female. El Portil (Huelva).

Preparing the gallery for laying the eggs. Punta Umbría (Huelva).

Eggs being laid. Nuevo Portil (Huelva).

The clutch, detail. Punta Umbría (Huelva).

Newly hatched. Nuevo Portil (Huelva).

Newly hatched. Nuevo Portil (Huelva).

Specimen just a few days old. Nuevo Portil (Huelva). Photos: © J. P. González de la Vega.

The eggs are laid in a hole in the ground under a bush, excavated by the female using the forelimbs. As this work is extremely laborious due to the shape of the limbs, the construction of the gallery takes several hours of work, so in most cases they spend the night inside it. By early next morning, everything has been completed and has been well concealed.

The clutch consists of between 5 and 46 eggs (Schleich et al., 1996). The data relating to Western Andalusia are between 6 and 26 eggs, (JP Gonzalez de la Vega, unpublished data), maximum 43 (M. Cuadrado, pers..) The eggs are white, gummy and somewhat elliptical measuring from 8 to 12.5 mm x aged 10-19 (Schleich et al., 1996), 14.6 x 11.5 to 23.1 x 12.7 mm for Western Andalusia (JP Gonzalez de la Vega, unpublished data). Since the months following the conception coincide with the lowest temperatures of the year, the actual incubation begins well into the month of April. Hatching occurs between 350 and 360 days (Schleich et al., 1996), or between 258 and 377 days after being laid (Western Andalusia; JP Gonzalez de la Vega, unpublished data). Infants in Western Andalusia, have a size between 50 and 75 mm in total length (JP Gonzalez de la Vega, unpublished data). They reach sexual maturity at one year of life. The maximum age is estimated at five years or seven years (Cuadrado, 2009).

The annual period of activity generally runs between March and November. Hibernation takes place in the hollows of trees, under leaf litter, among piles of stones or under, between or under rocks, or simply in any ground cavity. If temperatures are favorable, they can be seen sunning themselves on warmer days, even if the winter is extremely cold, and may remain active throughout the year.

| BIOMETRIC DATA AND REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY: Common Chameleon Chamaeleo chamaeleon (Linnaeus, 1758) | |

| Adult Weight | Between 14 & 88 g (not including pregnant females) |

| No of Eggs per clutch | Between 6 & 26 eggs. Max 43 (M. Cuadrado, com. pers.) |

| Eggs Laid | From 15 September to 18 November |

| Size of Eggs | Between 14.6 x 11.5 & 23.1 x 12.7 mm |

| Weight of Eggs | Between 0.82 & 1.91 gr |

| Time for Incubation | Between 320 & 377 days |

| Size of Newborn | Between 50 & 75 mm in length (from head to tip of tail) |

| Weight of Newborn | Between 0.65 & 1.55 gr |

Reference data for the species from Western Andalucia

© J. P. González de la Vega, unpublished data

Distribution, habitat and abundance

The Chameleon is mainly distributed around the Mediterranean. It is present in the south of the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily, Malta, Greece and certain Mediterranean islands, presumably the result of ancient introductions. In Morocco it is widely distributed and occupies almost all the bioclimatic range from sea level to 1,800 m in the High Atlas. It is a relatively common and abundant species in certain areas but populations are declining due to the degradation and destruction of their habitats.

Apart from natural enemies (certain birds, mammals and reptiles), the greatest enemy of the common chameleon is motor traffic, since it has been shown that every year a large number are run over when attempting to cross the increasingly numerous roads. This happens especially during the breeding season as this is the time when movements are more frequent, males are seeking out females, less dominant males fleeing or gravid females moving to find an ideal place in which to deposit eggs, and so on.

The highways are source of danger for the species and annually a large number die after being hit by vehicles.

Top left: Guercif. Photo: © J. P. González de la Vega. Top right: Tiz´n´Test. Photo: © Gabri Mtnez.

Bottom left: Entre Aklim y Madagh. Photo: © J. P. González de la Vega. Bottom right: Er-Rachidia. Photo: © Gabri Mtnez.

On the other hand, a large number of specimens are captured for sale in souks and traditional herbalists in the belief that the use of certain animal parts mixed with food can restore the union of a couple going through bad times, as protection against “evil eye” or simply as a tonic to strengthen the weak. In this way, the captured specimens are offered for sale, very much alive and caged, well fed, in the “Berber pharmacies” where they are used for making potions and other supposed remedies of traditional medicine related to witchcraft and magic.

According to the IUCN criteria it is not on the list of species requiring special protection. In the Western Sahara it is listed as “Vulnerable”, while worldwide is classified as “low risk-near threatened” (Geniez et al., 2004).

Translated from Spanish by Hazel Skeet.

References

- Bons, J. & Geniez, P. 1996. Anfibios y Reptiles de Marruecos. Asociación Herpetológica Española, Barcelona. 319 pp.

- Cuadrado, M. (2009). Camaleón común – Chamaeleo chamaeleon. En Enciclopedia Virtual de los Vertebrados Españoles. Salvador, A., Marco, A. (Eds.). Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales. Madrid. http: //www.vertebradosibericos.org/

- Geniez, P.; Mateo, J.A.; Geniez, M. & Pether, J. 2004. The amphibians and reptiles of the Western Sahara. Edition Chimaira, Frankfurt, 228 pp.

- González de la Vega, J. P. 1988. Anfibios y reptiles de la provincia de Huelva. Ertisa, Huelva. 238 pp.

- Paulo, O. S., Pinto, I., Bruford, M. W., Jordan, W. C., Nichols, R. A. 2002. The double origin of Iberian peninsular chamaeleons. Biol. J. Linn. Soc., 75: 1-7.

- Salvador, A. 1998. Chamaelelo chamaeleon (Linnaeus, 1758). Pp. 129-135. En Salvador, A. (Coord.). Reptiles. Fauna Ibérica. Vol. 10. Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, Madrid.

- Schleich, H. H., Kästle, W. & Kabisch, K. 1996. Amphibians and Reptiles of North Africa. Koeltz Sci. Books, Koenigstein. 630 pp.

To cite this page:

Juan Pablo González de la Vega (2012): Chamaeleo chamaeleon (Linnaeus, 1758). In: Martínez, G., León, R., Jiménez-Robles, O., González De la Vega, J. P., Gabari, V., Rebollo, B., Sánchez-Tójar, A., Fernández-Cardenete, J. R., Gállego, J. (Eds.). Moroccoherps. Amphibians and Reptiles of Morocco and Western Sahara. Available from www.moroccoherps.com/en/ficha/Chamaeleo_chamaeleon/. Version 23/09/2012.

To cite www.morocoherps.com en as a whole:

Martínez, G., León, R., Jiménez-Robles, O., González De la Vega, J.P., Gabari, V., Rebollo, B., Sánchez-Tójar, A., Fernández-Cardenete, J.R., Gállego, J. (Eds.). Moroccoherps. Amphibians and Reptiles of Morocco and Western Sahara. Available from www.moroccoherps.com.