Moorish viper

Daboia mauritanica (Duméril & Bibron, 1848)

By Gabriel Martínez del Mármol Marín

Updated: 23/10/2013

Taxonomy: Serpentes | Viperidae | Daboia | Daboia mauritanica

Daboia mauritanica

Daboia mauritanica

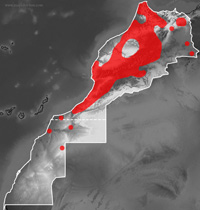

Distribution map of

Daboia mauritanica

in Morocco.

Gallery: 5 photos. [ENTER]

Phylogenetic frame

This large snake was first described as Echidna mauritanica, by Dumeril & Bibron (1848). Later, some authors considered it to be a subspecies of Macrovipera lebetina (Schwarz , 1936, Harding & Welch, 1980; Obst, 1983) while others treated it as its own species within the genera Vipera or Macrovipera (Sochurek , 1979; Herrman, Joger & Nilson, 1992, Welch, 1994; Bons & Geniez, 1996 ) (Uetz & Hosek, eds). Recent genetic analyses include it in the genus Daboia (Lenk et al., 2001; Garrigues et al., 2005; Wüster et al., 2008; Stumpel N. & Joger, U., 2011), although due to the few samples the species used in this analysis, it is not yet possible to learn about the genetic diversity in Daboia mauritanica nor its relationship with Daboia deserti (Jiménez Robles & Martínez del Mármol, 2013).

Description

Daboia mauritanica is the longest viper found in the study area, growing up to 181 cm total length in the wild (Geniez et al., 2004). Although it usually does not exceed 130 cm, captive specimens have come to reach 240 cm (Schleich et al., 1996).

The head is large and well differentiated from the body. The top of the head is composed of many small keeled scales similar to the dorsal scales. The eyes are relatively large with a vertical pupil. It normally has a band of colour, darker than the background colour, running from the end of the jaw to the nostrils passing through the temporal region and eyes (the latter typically display two tones, one clearer in the upper half and a darker colour, like the colour of the band, in the lower half , giving the band continuity). It may also have other spots between the eyes and on the 3-5th supralabials and between the nostrils and the first supralabials. The colouring of the head is certainly an important part of the amazing camouflage strategy that allows these large animals in their habitats to pass unnoticed by prey and predators.

Left: Detail of juvenile. Guelmim. Photo: © Gabri Mtnez. Right: Detail of adult. Agadir. Photo: © Raul León Vigara.

Left: Top view of the head. Agadir. Photo: © Gabri Mtnez. Right: Bottom view of the head. Agdz. Photo: © Victor Gabari Boa.

The body is elongated but solid and composed of 27 rows of dorsal scales along the center of the body (Schleich et al., 1996). It has a variable coloration but usually greyish or brown. Exceptionally some individuals have very red colorations (Guelmim, Ouarzazate, J. Timms, pers. comm.), and greenish specimens are also known in the region of Taroudant (JA Valverde, unpublished). It is well known for a pigmentation pattern along the dorsal area consisting of more or less circular spots and arranged in zigzag. The contrast between that zigzag and the background colour depends on the populations and the age of the individual, fading to being absent in some individuals (older specimens often have duller colours while juveniles are often more contrasted). Although there are exceptions, generally in the northern Atlas strongly contrasted individuals have been found while south of the Atlas specimens are typically “pale” (a “pale” morph was described for individuals of the Anti-Atlas and south-western end of the range; Geniez et al. in Bons & Geniez, 1996). Both forms are found between Agadir and Tantan, where there is a greater variety of designs and colours.

Left : Contrasted Individual. Casablanca. Photo: © Gabri Mtnez. Right: “Pale” Individual. Ouarzazate. Photo: © Mario Schweiger.

The scales at the tip of the tail end of some specimens, have a striking granular appearance (eg on a specimen found in the region of Casablanca ) and in many cases are a different colour (yellow only in the “belly” in the specimen of Casablanca and yellowish entirely in a young specimen found in the region of Figuig). This could mean the tail is used as a tactical lure as is already known for other snakes, eg many viperids (Allen, 1949; Wharton, 1960, Greene and Campbell, 1972; Heatwole and Davison, 1976; Parellada & Santos 2001), including Daboia russelli (Henderson , 1970).

Tail detail. Casablanca. Photos: © Gabri Mtnez.

Tail detail. Figuig. Photos: © Gabri Mtnez.

Ecology and habits

The snake is a species eminently suited to the Maghreb environment and can be active in the daytime, at dusk and in the early evening hours. In autumn and spring it can be found at the foot of solea scrub, rock crevices or in burrows but never far from shelter. In the region of Oran (Algeria) it has a period of hibernation or diapause during the colder months of the year, starting its activity again in March (Schleich et al., 1996). In Morocco it also must have a period of inactivity (total or partial depending on the altitude and the weather) in the colder months, having their high activity periods in the months of April to June and September to October.

Daboia mauritanica feeds mainly on lizards, birds and small mammals (Schleich et al., 1996). Many of the observations were in areas where there were large colonies of Moorish squirrels (Atlantoxerus getulus), which could also be one of their prey. On the outskirts of Casablanca a case is known in which some farmers killed an adult of this species found among the plates of corrugated iron that served as a chicken coop. They claimed that this species frequently preys on the chicks.

Among its predators are pigs and wild boar (Sus scrofa) (Schleich et al., 1996). In the vicinity of Agadir, in June 2011, the dead body of young adult was found in an irrigation ditch along with an adult female Malpolon monspessulanus saharatlanticus with a relatively bloated stomach. The latter being the only snake found in such constructions and as the snakes cannot exit the ditch due to the verticality of its walls it appeared that the female had preyed on the Daboia mauritanica (this behaviour has already been noted for the Montpellier snake as predator of other viperids, eg Vipera latastei; Barbadillo, 1987).

Copulation usually takes place in the month of May (Schleich et al., 1996). It is an oviparous species. Near Agadir, an adult female was found next to a set of 11 white rounded eggs (R. Leon Vigara & G. Martinez del Marmol, unpublished). They can lay up to 21 eggs (Mateo- Miras et al., 2006).

Left : Clutch in poor condition . Agadir. Photo: © Raul León Vigara . Right: Juvenile. Guelmim . Photo: © Baudilio Fernández Rebollo.

It is an elusive snake whose habits mean it can easily pass unnoticed. But it often inhabits crop edges, farms and humanized areas where it is often found by humans. The aggressiveness of some individuals and the potency of their poison (the bite can be fatal to humans) is usually known by the local people. In some locations people actually demolish walls and other constructions to facilitate this killing (although Pleguezuelos & Fahd (2001) comment that local people never confuse them with other snakes, we thought that generally many harmless snakes -especially Natrix maura and Hemorrhois hippocrepis – must be killed as they are mistaken with the Moorish viper).

Distribution, habitat and abundance

It is endemic in the Maghreb (Morocco – including some sites in the Western Sahara-, Algeria and Tunisia), although the limits of its distribution are not clear yet (Jiménez Robles & Martínez del Mármol, 2013). In Morocco it is the viperid with the widest distribution, being found from sea level up to 2300 m, although in the Rif it is more abundant in the altitude between 200-600 m (Pleguezuelos & Fahd, 2001; Bons & Geniez, 1996). It is very commonly found in arid and semiarid bioclimatic conditions, while in the humid floor it is rarer (Bons & Geniez, 1996). In Jebel Grouz in Figuig region, it was found recently (Vigara León, R. & Martínez del Marmol, G., unpublished) confirming the report of 1922 (Foley in Bons & Geniez, 1996).

This species is very common in many habitats but seems more abundant in rocky biotopes around rivers, where they find lots of shelter and food. It shelters in walls usually with thorny bushes and probably has been helped by the massive planting of Opuntia ficus-indica in much of its range, which serves as a shelter in rocky biotopes with low shrub cover (Marrakech, Agadir, Tafraoute, Tiznit, Sidi Ifni… ). From Agadir in the north to south of Tantan it is relatively abundant in the landscape of Atlantic influenced steppes dominated by Euphorbia officinarum subsp. echinus type plants and where there are plenty of mammals nesting. According to recent finds it shares habitat with another large viper, Bitis arietans, and although Moorish Viper has predilection for rocky biotopes over the puff adder, both can live together on the beds of wadis and other areas of sand and bushes where they can also share habitat with the horned viper (Cerastes cerastes). This sharing of habitat does not happen in mountainous areas of northern Morocco between Daboia mauritanica and Lataste´s vipers (Vipera latastei – monticola complex) (Pleguezuelos & Fahd , 2001 ).

Left: Typical habitat around Casablanca. Right: Typical habitat around Marrakech. Photos: © Gabri Mtnez.

Left: Typical habitat around Agadir. Right: Typical habitat around Guelmim. Photos: © Gabri Mtnez.

Left: Typical habitat around Agdz. Right: Typical habitat Figuig around. Photos: © Gabri Mtnez.

Although their distribution in Morocco is broad, automatic annihilation at the hands of humans for probably thousands of years means that it has become very elusive animal and difficult to locate. Most encounters involve finding the bodies that have been run over on a road or track. Other problems include death by falling into pits, cisterns and other human constructions to retain water. They are also caught by Aissaoua, who sell them to the snake charmers for the shows, but his temperament makes them less desirable than Bitis arietans (nevertheless estimated 230-345 plundering individuals per year; Feriche, Aisauas: snake charmers ). All these factors mean that despite being still relatively abundant, the population is declining significantly, its condition is considered today as “Near Threatened” ( NT : Mateo-Miras et al., 2006 ).

Acknowledgements

Fernando Martínez Freiría for his contributions to the development of this page.

Translated from Spanish by Hazel Skeet.

References

- Allen, E.R. 1949. Observations of the feeding habits of the juvenile cantil. Copeia 1949: 225-226.

- Barbadillo, L. J. 1987. La Guía de Incafo de los Anfibios y Reptiles de la península Ibérica, Islas Baleares y Canarias. Incafo, Madrid. 694 pp.

- Bons, J. & Geniez, P. 1996. Amphibiens et reptiles du Maroc (Sahara Occidental compris). Atlas Biogéographique. Asociacion Herpetologica Espanola, Barcelone. 319 pp.

- Garrigues, T.; Dauga, C.; Ferquel, E.; Choumet, V. & Failloux, A-B. 2005. Molecular phylogeny of Vipera Laurenti, 1768 and the related genera Macrovipera (Reuss, 1927) and Daboia (Gray, 1842), with comments about neurotoxic Vipera aspis aspis populations . Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution Volume 35 (1): 35-47

- Geniez, P.; Mateo, J.A.; Geniez, M. & Pether, J. 2004. The amphibians and reptiles of the Western Sahara (former Spanish Sahara) and adjacent regions. Edition Chimaira, Frankfurt, 228 pp.

- Greene, H. W. & Campbell, J. A. 1972. Notes on the use of caudal lures in arboreal green pit vipers. Herpetologica 28: 32-34.

- Heatwole, H. & Davison, E. 1976. A review of caudal luring in snakes with notes on its ocurrence in the Saharan sand viper, Cerastes vipera. Herpetologica 32: 332-336.

- Henderson, R.W. 1970. Caudal luring in a juvenile Russell’s viper. Herpetologica 26: 276-277

- Jiménez Robles, O. & Martínez del Mármol Marín, G. 2013. Comments on the large paleartic vipers Macrovipera and Daboia in North Africa. Published on March 05, 2012. Updated on April 23, 2012. Available from http://blog.moroccoherps.com/vipers-macrovipera-and-daboia-in-north-africa. Accessed May 22, 2013.

- Lenk, P.; Kalyabina, S; Wink, M. & Joger, U. 2001. Evolutionary relationships among the true vipers (Reptilia: Viperidae) inferred from mitochondrial DNA sequences. Molecular Phylogenics and Evolution. 19 (1): 94-104.

- Miras, J. A. M.; Joger, U.; Pleguezuelos, J. & Slimani, T. 2006. Daboia mauritanica. In: IUCN 2012. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2012.2. . Downloaded on 25 May 2013.

- Parellada, X. & Santos, X. 2002. Caudal luring in free-ranging adult Vipera latasti. Amphibia-Reptilia 23 (3): 343-347

- Pleguezuelos, J.M. & Fahd, S. 2001. Los reptiles del Rif (Norte de Marruecos), II: anfisbenidos y ofidios. Comentarios sobre la biogeografía del grupo. Revista Española de Herpetología 15: 13-36.

- Schleich, H. H.; Kastle, W. & Kabisch, K. 1996. Amphibians and Reptiles of North Africa. Koeltz Scientific Publishers, Koenigstein. 630 pp.

- Stümpel N. & Jöger, U. 2011. Phylogeny and phylogeography of Near and Middle East vipers (Daboia, Montivipera and Macrovipera). European Congress of Herpetology & Deutscher Herpetologentag.

- Uetz, P. & Jirí Hošek (eds.). Macrovipera mauritanica (DUMÉRIL & BIBRON, 1848). The Reptile Database, http://www.reptile-database.org. Accessed on 22-5-2013).

- Wharton, C.H. 1960. Birth and behavior of a brood of cottonmouths, Agkistrodon piscivorus piscivorus with notes on tail-luring. Herpetologica 16: 125-129.

- Wüster, W.; Peppin L.; Pook, C.E. & Walker, D.E. 2008. A nesting of vipers: Phylogeny and historical biogeography of the Viperidae (Squamata: Serpentes). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 49 (2): 445-459.

To cite this page:

Gabriel Martínez del Mármol Marín (2013): Daboia mauritanica (Duméril & Bibron, 1848). In: Martínez, G., León, R., Jiménez-Robles, O., González De la Vega, J. P., Gabari, V., Rebollo, B., Sánchez-Tójar, A., Fernández-Cardenete, J. R., Gállego, J. (Eds.). Moroccoherps. Amphibians and Reptiles of Morocco and Western Sahara. Available from www.moroccoherps.com/en/ficha/Daboia_mauritanica/. Version 23/10/2013.

To cite www.morocoherps.com en as a whole:

Martínez, G., León, R., Jiménez-Robles, O., González De la Vega, J.P., Gabari, V., Rebollo, B., Sánchez-Tójar, A., Fernández-Cardenete, J.R., Gállego, J. (Eds.). Moroccoherps. Amphibians and Reptiles of Morocco and Western Sahara. Available from www.moroccoherps.com.