Agadir Gecko

Saurodactylus brosseti Bons & Pasteur, 1957

By Victor Gabari (Original: 23/09/2012)

Updated: 23/03/2020 (by Gabriel Martínez del Mármol)

Taxonomy: Gekkota | Sphaerodactylidae | Saurodactylus | Saurodactylus brosseti

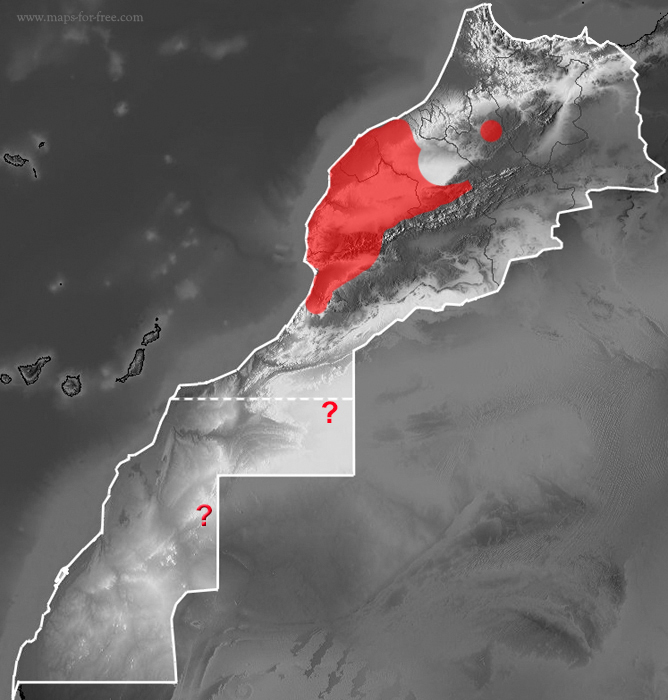

Saurodactylus brosseti (sensu stricto after Javanmardi et al., 2019)

Saurodactylus brosseti (sensu stricto after Javanmardi et al., 2019)

? Populations assigned provisionally to this species.

Photo gallery: 35 photographies (including photos of all the species described within Saurodactylus brosseti species complex). [ENTRAR]

Phylogenetic frame

Although some authors have considered it a subspecies of Saurodactylus mauritanicus (Duméril & Bibron, 1836), Bons & Geniez (1996) elevated it to species rank, which seems to have been accepted by most authors (Geniez et al., 2004; Sindaco & Jeremencko, 2008).

Subsequently, its specific range was demonstrated by genetic analyzes (Rato & Harris, 2008), which also show that the allocation of this genus in the family Sphaerodactylidae Underwood, 1954 is not entirely clear and its taxonomic position is still highly uncertain.

Recently, new genetic studies proved that Saurodactylus brosseti is actually a species complex (Rosado et al., 2017), which has led to the description of 4 new species within this complex (Javanmardi et al., 2019): Saurodactylus harrisii for the coastal populations south of Tiznit, Saurodactylus elmoudenii for the Antiatlas mountains, Saurodactylus splendidus for the mountainous areas in the Icht area, Saurodactylus slimanii for the populations east of the Antiatlas mountains, leaving the distribution of Saurodactylus brosseti sensu stricto for the Souss Valley and the populations North of the High Atlas Mountains.

Description

(Note that the description may not respond exclusively to individuals belonging to this clade)

Small gecko that reaches a maximum size of 31 mm in maximum snout-vent length and 67.5 mm in total length (Schleich et al., 1996).

The head is relatively large, undifferentiated from the neck, and has two large eyes with a vertical pupil. A more or less broad yellow line stands out on each side of the head, which in most individuals goes from the nostrils to the first third of the body, passing through the eyes as a “brow.” The supralabials and the throat are whitish.

The body is robust and composed of small, flat and smooth dorsal scales. In the dorsal part, small yellow-orange ocelli stand out. The ventral scales are white, large, hexagonal, rounded, and imbricate. 70-90 scales are counted around the central part of the body (Schleich et al., 1996). The extremities are relatively strong and lack adhesive sheets, adapted to the excavating habits of this species. The tail, yellowish-orange in color, has brown or brown spots.

The dorsal coloration is very variable: shades of orange, gray-brown or dark brown on which small ocelli stand out, most of them arranged in 2 longitudinal lines. The dorsal and caudal pigmentation is markedly separated at the base of the tail. The coloration has been described as having a marked sexual character: males are dark brown with golden dots, females are light brown to gray (Schleich et al., 1996).

Ecology and habits

It is a species very adapted to extremely arid areas, and is able to withstand heat, drought and hunger for several months. It has been found under small stones even in the hottest months and when the ambient temperature exceeded 40º. Under these it finds the necessary humidity to survive and avoids most of its predators (Meek, 2008).

It is active before dawn and during twilight (Schleich et al., 1996).

Patterns of social behavior have been described, the most frequent signs being arching the back, raising and waving the tail. The threatening gesture can be frontal or lateral (Schleich et al., 1996).

This species is a fierce predator in relation to its size. This behavior can be interpreted as an adaptation to the arid environment. Prey on small insects and arachnids (Schleich et al., 1996).

From May to September, laying can occur every 4 weeks, consisting of 1 egg. The egg is deposited at the end of a short tunnel in the ground made by themselves (Schleich et al., 1996).

Given its small size, it must be the prey of a multitude of small or medium-sized vertebrates. Predation data have been recorded for Malpolon monspessulanus and Macroprodon “cucullatus” (Schleich et al., 1996) and possibly scorpions (Meek, 2008). When he feels threatened, he tries to focus attention on his tail, with a different coloring than the rest of the body. It moves it quickly and begins to flee at high speed to a nearby refuge, being able to detach itself from the tail in case of being attacked by the predator. They can also shed skin fragments very easily, which could be due to a defensive mechanism similar to caudal autonomy.

Distribution, habitat and abundance

It´s probably an endemic of Morocco, inhabits from El Jadida and Azilal in the north, to Agadir, and possibly Tiznit to the south, including the entire Souss valley.

This species is found up to 1900m (Joger et al., 2006).

It lives in open fields and agriculture fields, under stones or in the roots of plants. It is common in natural areas but also in areas altered by man as cultivation fields and is very frequent in plantations of Opuntia ficus-indica Linnaeus, 1768.

It is a very common species in its range, which does not seem to present conservation problems (Least Concern; LC; Joger et al., 2006).

Bibliography

- Bons, J. & Geniez, P. 1996. Anfibios y Reptiles de Marruecos (Incluido Sahara Occidentales). Atlas Biogeográfico. Asociación Herpetológica Española. Barcelona. 319 pp.

- Barnestein, J.A.M, González de la Vega, J.P, Francisco Jiménez-Cazalla, F & Víctor Gabari-Boa 2010. Contribución al atlas de la herpetofauna de Marruecos. Bol. Asoc. Herpetol. Esp. (2010) 21.

- Duméril, A.M. C. & G. Bibron. 1836. Erpetologie Générale ou Histoire Naturelle Complete des Reptiles. Vol.3. Libr. Encyclopédique Roret, Paris, 528 pp.

- Geniez, P.; Mateo, J.A.; Geniez, M. & Pether, J. 2004. The amphibians and reptiles of the Western Sahara (former Spanish Sahara) and adjacent regions. Edition Chimaira, Frankfurt, 228 pp.

- Javanmardi, S.; Vogler, S.; Joger, U. 2019. Phylogenetic differentiation and taxonomic consequences in the Saurodactylus brosseti species complex (Squamata: Sphaerodactylidae), with description of four new species. Zootaxa 4674 (4): 401–425

- Joger, U., Slimani, T., El Mouden, H. & Geniez, P. 2006. Saurodactylus brosseti. In: IUCN 2011. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.2. . Downloaded on 14 January 2012

- Meek, R. 2008. Retreat site characteristics and body temperatures of Saurodactylus brosseti Bons & Pasteur, 1957 (Sauria : Sphaerodactylidae) in Morocco. Bull. Soc. Herp. Fr. (2008) 128 : 41-48

- Rato, C; Harris, D.J. 2008. Genetic variation within Saurodactylus and its phylogenetic relationships within the Gekkonoidea estimated from mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequences. Amphibia-Reptilia 29 (1): 25-34

- Rosado, D; Rato, C.; Salvi, D.; Harris, D.J. 2017. Evolutionary history of the Morocco lizard-fingered geckos of the Saurodactylus brosseti complex. Evolutionary Biology, 44 (3), 386–400.

- Schleich, H.H.; Kästle, W. & Kabisch, K. 1996. Amphibians and Reptiles of North Africa. Biology, Systematics, Field Guide. Koeltz Scientific Books. 630 pp.

- Sindaco, R. & Jeremcenko, V.K. 2008. The reptiles of the Western Palearctic. Edizioni Belvedere, Latina (Italy), 579 pp.

To cite www.moroccoherps.com as a whole:

Victor Gabari (2012): Saurodactylus brosseti Bons & Pasteur, 1957. En: Martínez, G., León, R., Jiménez-Robles, O., González De la Vega, J. P., Gabari, V., Rebollo, B., Sánchez-Tójar, A., Fernández-Cardenete, J. R., Gállego, J. (Eds.). Moroccoherps. Anfibios y Reptiles de Marruecos y Sahara Occidental.

Disponible en www.moroccoherps.com/ficha/Saurodactylus_brosseti/. Versión 23/03/2020. Consulta realizada el 15 de enero de 2020.